Savernake FOREST

Volume VIII Chapters

- Safernoc

- The Esturmy Wardens

- The Bailiwicks of Savernake

- The Dowager Queens

- The Perambulation of 1244

- The Perambulation of 1330

- Sir Robert Bilkemore

- Parks and Warrens

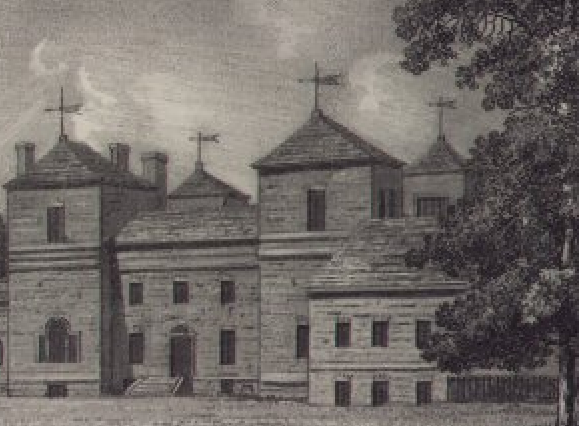

- Tottenham Lodge